The Herb Paris Project 2006 by Meryl Beek

Have you ever wondered why Herb Paris (Paris quadrifolia) appears on the front cover of The Reading Naturalist? Correspondence with Dr Leonard Williams, who was the first editor from 1949 to 1953 has the answer. There were several special plants that the Society’s “Discussion Group” in the 1940’s and 50’s kept an eye on every year. These were the Fritillary meadow at Sandford Mill, the Pasqueflower colony on Moulsford Down and Herb Paris at Maidensgrove Scrub. It was felt that one of these should be chosen as the emblem, and member Paul Betts, a friend of Leonard Williams, thought Herb Paris would provide the best design. As he was a professional commercial artist, his opinion was accepted; and it was on the cover of Issue No. 3 (1951) that the now familiar and attractive Herb Paris motif, prepared by Paul Betts, made its first appearance.

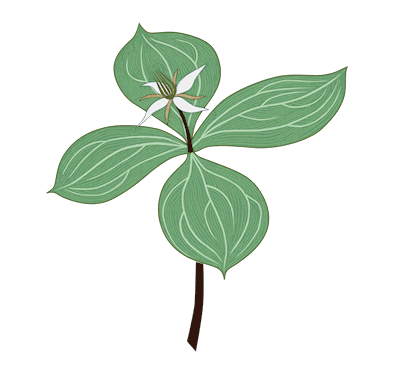

At a recent committee meeting it was suggested that it might be a good idea to look back at some of the old natural history records and update them. As a good beginning, and with the help of the Botany Recorder, a list of places where Herb Paris has grown in the past has been collated. The limits are the accepted 20 mile radius from Reading. The records for Herb Paris go back as far as the Berks Flora of 1897. RDNHS records are included, together with Atlas 2000 and the newer Berks and Oxon floras. Herb Paris is a comparatively rare plant, but it can be found flowering from late April to early June in dampish woods on alkaline soil. It is often, but not invariably, under Beech or Oak trees and the leaves can be detected in the undergrowth from March, mixed up with Dog’s Mercury.

Herb Paris comes from the Latin par meaning “equal” and refers to the regular symmetry of the plant. In medieval times, medicine was based on the Doctrine of Signatures. Quite reasonably it was believed that a beneficent God had created a range of wild herbs with curative properties for all the world’s ills. Each was coded with a “sign” or “signature” indicative of the disorder for which it was the remedy. The symmetry of Herb Paris signified its effects against “disorder” as caused by witches and epileptics! (Thames Valley Police’s logo is “Reducing crime, fear and disorder” which shows how little has changed!)

Herb Paris – A Quick Flit through History by Linda Carter

There is a mysterious allure about the cradled golden flower, in its crown of leaves, atop the single stem that renders Herb Paris unforgettable. Although never a common, or even very widespread, species it has attracted the attention of herbalists and botanists alike, throughout recorded history.

To the Medieval herbalists, it was the numerical harmony of the parts of Herb Paris that appealed so strongly. No wonder they named it herba paris, ‘pair herb’, for it bears twice two leaves, twice four stamens, twice two outer and twice two inner segments to the perianth, twice two styles and twice two cells to the ovary.

William Turner, often referred to as the ‘father of English botany’, was the first to record this plant in Britain. He grew up in Morpeth in Northumberland, coming south to study to be a physician at Cambridge. There, he became embroiled in the religious ferment of his time and was ordained into the priesthood. In 1548 he named Herb Paris ‘Libardbayne or one bery. It is much in Northumberland in a wodd besyde Morpeth called Cottingwod.’ Cotting Wood exists to this day, but we no longer confuse Herb Paris with Leopard’s-bane. It remained for Henry Lyte, translating the Herbal of Dodoens into English, in 1578, to translate the apothecaries’ Latin ‘herba paris’ into the accepted common name of today, ‘Herb Paris’.

Paris quadrifolia is often dubbed ‘True-love’ or ‘True-lover’s Knot’. Culpeper enlightens us as to the meaning of the true-love’s knot. He tells us that ‘at the top there are four leaves set directly against another, in the manner of a cross or ribband tied, in a true-love’s knot’. In Perth, the local name was ‘Devil-in-a-bush’, presumably from the poisonous berry sitting in the centre of the leaves. Amongst the many herbaceous plants that acquired the generic name ‘grass’, Herb Paris is no exception, attracting the Somerset name of ‘Four-leaved Grass’.

Margaret Baker records a complex divination rite that developed round Herb Paris. Two girls sat in a room together from midnight to one o’clock. Each plucked hairs from her head, to match her age in years, and put them in a linen cloth with Herb Paris leaves. When the clock struck one, the girls burnt each hair individually, reciting:

I offer this my sacrifice,

To him most precious in my eyes,

I charge thee now come forth to me;

That I this minute may thee see.

This was intended to invoke the future husband who would walk round, before vanishing, though either girl could see the other’s lover.

The life of the physician in the first half of the seventeenth century was not a carefree one and Herb Paris was in the arsenal of herbal remedies called upon to combat infection. Culpeper informs us, in his ‘Complete Herbal’, that ‘the leaves are very effectual for green [gangrenous] wounds, and to heal filthy old sores and ulcers, and powerful to discuss all tumours and swellings in the privy parts, the groin, or any other part of the body, and to allay all inflammations. The juice of the leaves applied to felons [whitlows], or those nails of the hands and feet that have sores or imposthumes [abscesses] at the roots of them, heals them in a short time.’ Here was a herb, intoned Culpeper, ‘fit to be nourished in every good Woman’s garden.’

According to Mrs Grieve in 1931, the active constituent is a glucoside named Paradin, a toxic narcotic that, in large doses, causes nausea, vomiting, vertigo, delirium, convulsions, profuse sweating and a dry throat. Needless to say, she adds immediately that the drug should be used with great caution!

Overdoses have proved fatal to children and chickens alike and we do not recommend that you try any of the following at home! Small doses were used to treat bronchitis, coughs, rheumatism, cramp, and palpitation of the heart. The juice of the berries was considered efficacious in treating inflammation of the eyes. A cooling ointment derived from the seeds and the juice of the leaves was used to treat green wounds, tumours and inflammations, as in Culpeper’s day. The powdered root, boiled up in wine was believed to relieve colic, though perhaps the wine alone would have done as well.

All in all, Herb Paris is indeed, a powerful herb, an antidote to arsenic and, if you should happen to feel the effect of witchcraft encroaching on your sanity, a handful of berries will put it right – or simply wander in the woodland this spring, and see the first of this year’s Herb Paris unfurl its twice two leaves in the dappled sunlight.

The Herb Paris Project survey results

The survey took place in 2006 and 2007. A number of sites were visited where it had previously been recorded. Unfortunately only very few plants were found.

In 2006 it was only found at Warburg Nature Reserve, Bix but in Berkshire many thousands were found near the River Kennet at Thatcham.

In 2007 it was seen again at Thatcham in good numbers also at Berrick Trench near Nettlebed, Langley Hill north of High Wycombe and Howe Wood near Watlington but not found in many other former locations. It is a hard plant to spot and no doubt under recorded. It is often found near the very common Dog’s Mercury that looks similar from a distance. It is an ancient woodland indicator species. One clue that may help find it is that Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum multiflorum) that likes similar conditions is often found nearby.